de vita sua

a blog

Rome's newest museum

by John D. Muccigrosso

tl;dr

Rome’s newest museum is on the Celio and showcases the marble plan of the ancient city. It’s well worth a visit, though you won’t see anything but the plan inside.

Introduction

Rome opened a new archaeological museum this year, not something that happens every day. I visited back in January and wanted to write something up, but since it was early days, I figured I’d give them some time to work out the kinks and then go back. I got to do that last week on what may have been the last hot Sunday of the summer, so here’s the post.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Il Museo della Forma Urbis

Back in January the city of Rome had the grand opening of the newest of the city’s many museums. Like most of them, it is housed in a re-purposed building, this one on the Celian Hill (the Celio in Italian), not far from the Colosseum. Unlike most (all?) of them, it is dedicated to just one artifact from the past, the Severan marble plan, often referred to by the Latin Forma Urbis Romae, or Plan of the city of Rome, and sometimes called just Forma Urbis, as in the museum’s official title. The marble plan was an enormous map of the city, about 18x13m, made during the first decade of the third century under the Severan emperors, and incised on some 150 pieces of marble which were attached to a wall of the Temple of Peace (Latin Templum Pacis), now part of the Church of Saints Cosmas and Damian, flanking the Roman Forum site. The map was broken into thousands of pieces at some point(s) in the past, and over 1,000 of them have been recovered, though many are too small to be of much use. The museum highlights both the fragments themselves and the history of the discovery of the plan and scholarship on it.

The fragments have long (and notoriously) been unavailable for viewing by the public, so their display in a purpose-designed museum is notable and good news. I should also add that this is one of my favorite artifacts from ancient Rome, so I’m very happy about being able to see the fragments.

Tickets are available on-line (with the usual €1 additional fee) via the museum’s website, as well as at the museum itself. Full price is €9.50, with a €3 discount for residents of Rome. The museum is part of the Musei in Comune circuit, so residents with the MIC card get in for free.

Onto some details.

Location

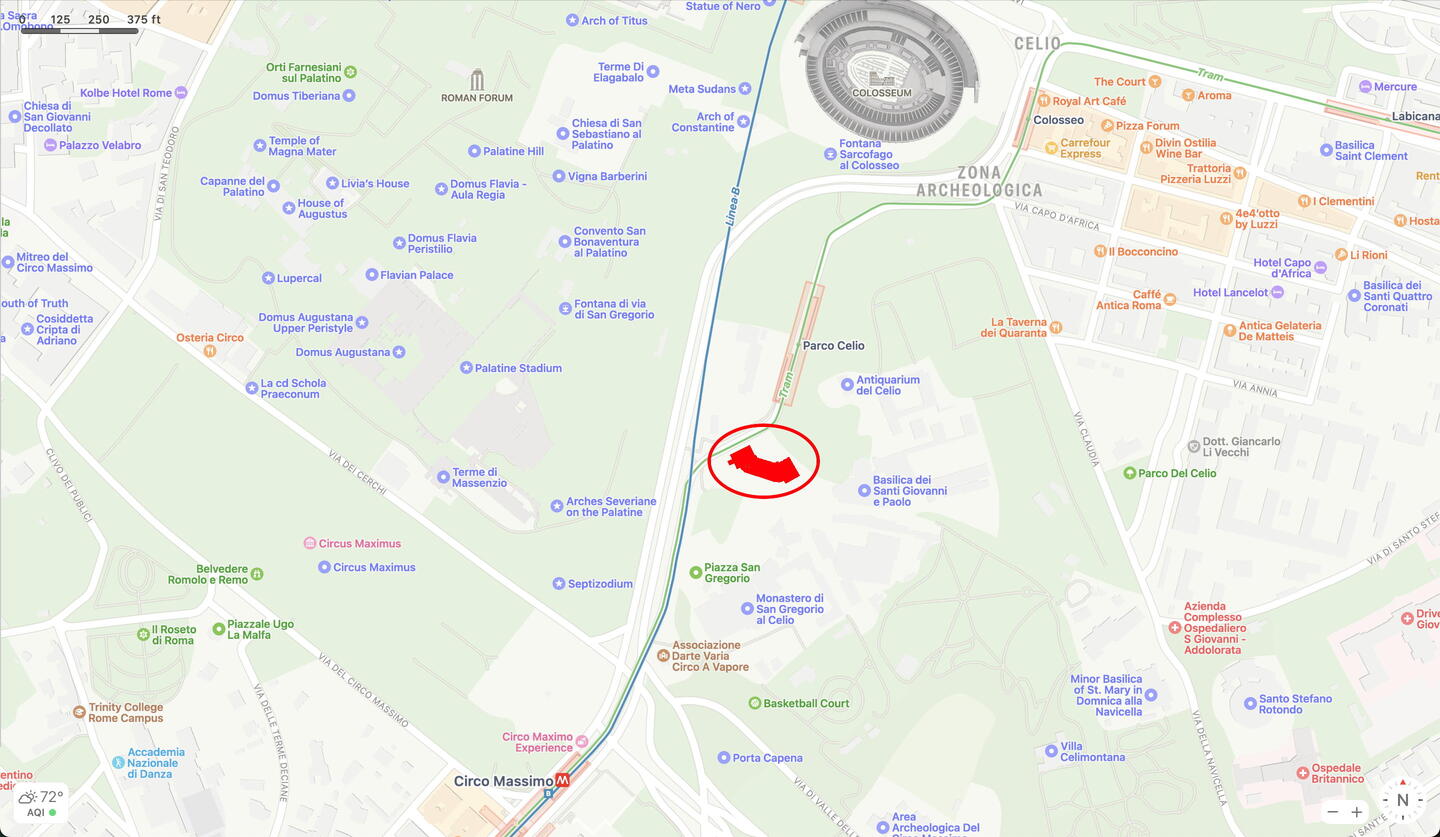

The museum is housed in the long-closed former Palestra della Gioventù Italiana del Littorio on the Celian. I’ve colored it red and circled it on the map here. It is in a wedge of the city that is been off the beaten path and without much motivation for the public to visit. The neighboring Antiquarium of the Celio has been closed for years, too. That said, it’s a convenient spot, just minutes on foot from a whole bunch of places: the Colosseum, the Circus Maximus, the entrance to the Forum/Palatine on Via di S. Gregorio, the much less visited church of Saints John and Paul (neither is an apostle or evangelist), the Roman houses of the Celian, the lovely park with what is probably Rome’s least seen ancient obelisk, and—off to the east—Santo Stefano Rotondo and the whole area leading off to St. John Lateran (which has been given a lot of love lately by the British School in Rome). The buses that run along the Via di S. Gregorio stop right by the stairs that lead up to the museum, and the 3 tram (when it’s running) stops almost right in front.

The museum is part of a larger fenced-in area that they’re calling the archaeological park of the Celian (Parco Archeologico del Celio), which includes two distinct areas near the museum. Off to your left as you enter, places to sit have been set up outside where there’s some shade from trees, and there’s also a gate giving access to the Clivus Scauri that leads east, past the Case Romane and church of John and Paul. This provides a nice pedestrian route through this part of the city. Straight ahead when you exit the museum (to the north), they’ve set up an outdoor area (I’m going to call it the “garden”) with lots of stone monuments or fragments thereof, most with inscriptions and many of them funerary. (This area backs up in part onto the remains of the substructure for the temple to the divine Claudius which in fact underlies a lot of the Celio.) Entrance to the park does not require a ticket, though the whole thing is inaccessible when the museum is closed.

This is a lovely area. When I visited in January, it was nice to walk around, look at the stones, and enjoy the sun. And you have to enjoy the sun, because there is zero shade in the garden. There are some benches, but not many. For about four to six months out of the year, this is probably not a place most people are going to linger, and frankly many people would probably need to be encouraged to linger in the first place. The (free-access) entrance area to the museum at the Baths of Diocletian, if you’re familiar with it, is based on a similar premise, though the setting there offers a lot more shade from trees and buildings and is in a very heavily trafficked zone. The objects in the garden also don’t have a lot of informational signs. The vast majority of them are completely unlabeled, so most people are not going to know what they’re looking at. Not great for a museum setting. Back in January 100% of them were without information, so the situation is improving. It’s too bad they’re missing, because some of the items are fairly interesting, if you’re into this sort of thing.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

Premise

Before going into the museum itself, I wanted to say a few words about the premise: this museum is a one-trick pony. It’s all about the Forma Urbis.

That’s it.

Now the Forma Urbis is a great thing, one of my favorites, as I said at the top, but still just one thing, and there isn’t anything else to see inside. This isn’t a museum with a star attraction and surrounding lesser luminaries, like the Galleria Borghese with its Bernini sculptures on top of a magnificent painting collection. Nope, it’s the Forma Urbis and that’s it. And that’s a problem, because the plan is not exactly on everyone’s bucket list.

There’s also the location. While it offers some advantages, as I just said, it’s off the usual tourist routes, hidden from the road. No one walks by here to get anywhere, and those that do may find themselves dodging the passing trams and occasional taxi. Several other close-by spots aren’t big tourist destinations either (though they should see more traffic than they do). Even academics like me are probably going to think twice about bringing students. If you go to this museum, you see one thing and then you have to travel again to see something else. Maybe you can visit some of the inscriptions in the garden or couple it with a trip to the Colosseum, but I suspect that it just won’t be seen as worth the effort by many.

When I went in January, there was a line. In part that’s because they were stopping everyone at the front door, but it was still a line. My totally unscientific sense was that the vast majority of people were Italian, many in tour groups, and many Romans. That lots of the people inside were looking to locate places they already knew in the modern city reinforced that sense. But last week, on a warm late-summer Sunday when the tourists were still pounding the hot pavement elsewhere in town, it was just me, one guy who was already there when I arrived, and a couple who came after me (and left before I finished). In fact it was so quiet outside that I thought the museum was closed.

It’s a small building, I realize, and maybe they were searching for something to fill it with. The Forma Urbis fits the bill on that account, and, truth be told, probably does need more space—and somewhat unusual space—than your average artifact. But I’m not sure it has the star power to carry its own museum. Even the museum of the Ara Pacis has a larger permanent collection and space for special shows as well, and that’s with a purpose-built museum that is in some ways its own attraction.

Time will tell, of course, but the drop-off in attendance from January to September isn’t encouraging.

Inside

The Main Room

The building has a gated forecourt with a few sculptural fragments in it. The structure itself seems to have been modernized for the museum with the addition of air conditioning (which worked well in the 32/90° heat when I was there…by myself), and the welcome inclusion of small lockers, bathrooms, and some vending machines.

It was designed with a gift shop as the entry space. When you come in the doors, the ticket booth is ahead of you, right by the large entryway that leads to the first and biggest gallery. The rest of the room is given over to the gift shop, something the Italians have finally caught onto. Items for sale include the usual collection of stuff for kids, some nice small posters, academic and popular books, and an assortment of tchotchkes.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I say “designed” as the entry space because they’re not really using it in this way. Instead of selling tickets (or taking your MIC card info) at the ticket booth, there’s someone at the door right when you enter. They were doing this in January, and I thought it might be because of the newness. Apparently not. I didn’t ask if they would let me in to browse the gift shop without a ticket—which I imagine was the idea in the design—and I’m not sure why they’re not using the ticket booth, which is common at Roman museums (as at others, of course). It may be the rest of the layout, but more on that in a bit.

The first and main gallery room is a large rectangular space with enormous windows in front of you, on its south side, and big industrial ducts running up the wall on the right, presumably for the HVAC. Most of the fragments of the Forma Urbis are very cleverly laid out under the plexiglass(?) floor with Giambattista Nolli’s 18th c. map of the city as a backdrop. The walls have several didactic panels (all in both Italian and English, as are the placards outside in the garden), including one explaining the choice of Nolli, and on the left wall is a ramp leading to a platform that gives you a view of the plan from a little higher up (~1 m). The room is otherwise lit with small spotlights on the ceiling. Given the huge amount of light that comes in the windows, I’m not sure they’re needed for much of the day.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

The challenge with the plan is how you display a giant, wall-sized map so that people can see it in detail while still getting a sense of its size and of the whole of it? The solution of walking over the map is an interesting one. For detail, visitors can crouch down and get fairly close to the fragments without being able to touch them. On the other end of the scale though, I’m not sure that it quite conveys the overall impression the plan must have made, especially since the fragments are embedded in an 18th c. map that’s impossible to miss.

The solution that’s often found for displaying mosaics in museums makes for an interesting comparison. In that case, artifacts that belong on the floor are put up on walls to make them easier to see (with the potential consequence that many people don’t realize they belong on the floor). A good example of that is the Alexander Mosaic from Pompeii in the archaeological museum in Naples. That particular mosaic has very small mosaic tesserae (tiles) and so a lot of detail that repays getting up close to it. There are some places where the mosaics are left on the floor, but you usually can’t walk on them, so you miss the up-close view. (There’s a good example on the upper floor of the Museo Centrale Montemartini on the Viale Ostiense.)

The Forma Urbis is a really big map, so I’m not sure that there is a good solution. This approach provides a good viewing experience and does give some sense of the overall size of the plan. Maybe it is the best one can hope for.

The lighting in the room is problematic. When the sun is shining, light and shadows streak across the floor from those south-facing windows, making it a little challenging to get a good view where they strike it. Reflected light from the shiny floor even noticeably illuminates the wall. There are no shades to minimize this.1 The spotlights on the ceiling also create very bright reflections that can impede the view. You can move your head around to avoid them, but if you want a photo, you’ll have to try to block them with your hand or with the help of friends. Blocking out the shadows from the sun is a little more difficult.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

I’m of two minds about the use of the Nolli map. On the one hand, it’s a great map of the city, with similar use of outlines as the Forma Urbis, and a great concern for accuracy. In some ways then, it’s a nice complement to the plan, especially where ancient monuments were visible and appear on it. The nerdy academic in me loves it. On the other hand, it is a few hundred years old and the city has obviously changed a lot in that period. For people looking for familiar landmarks, it can be a bit tricky to navigate, especially if what you’re looking for is in one of the many areas that were still vineyards or other unbuilt spaces in the 1700s. I don’t know that a set of satellite photos wouldn’t have worked better.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

One more thing about this room: as I noted, the fragments are under the floor. I don’t know whether this will prevent dirt, dust, and the occasional dead bug from getting in there. That would mean regular lifting of the floor and cleaning around the fragments. We’ll have to see how it goes.

The Smaller Room

You leave this gallery via a door in the left wall relative to the entranceway. This leads to another, smaller rectangular room that has a few didactic wall displays, mainly to do with the mounting of the marble slabs on the walls at the Templum Pacis/Church of Cosmas and Damian. Here, as in the big gallery’s wall displays, you can get up close to some of the fragments without any intervening plexiglass. At the end of this room, you come to a sort of small foyer, back at the front of the building where an exit door is located, having made a kind of U-shaped path through the building. To your right is access to the eastern wing of the museum with lockers, vending machines, and bathrooms. To your left is a short corridor that leads back to the entrance area (the gift shop). Two didactic panels cover the walls to your left and right in the corridor, the right showing a drawing of Piranesi’s with many of the fragments on it, and the other giving a short history of the discovery and subsequent display of the fragments.

(Image by John D. Muccigrosso CC BY-NC-SA 4.0)

This is where you can really sense the challenges of the building. Obviously if you want to put your bag in a locker or hit the bathroom before your visit, you do that right after you enter, cutting from the gift shop through the short corridor and the foyer, and then you return to the shop where you enter the main gallery (ideally ignoring the other access through the smaller gallery). So that short corridor can’t be one-way. This may be why they’re taking tickets at the door: once you’re inside the building, you can go through that corridor to access the lockers, bathrooms and galleries, thus bypassing the ticket booth. It feels like the designers may have had a different idea in mind, or didn’t quite realize the implications of this layout, or maybe they did and couldn’t figure out a good way around it. There was a staff person at that exit door in the foyer, perhaps to prevent entrance there, but it would be a lot to ask them to make sure that everyone going through that area already had a ticket, especially when your MIC card means you don’t get one.

Conclusion

If you’re at all interested in the Forma Urbis, this is a nice place to see it in. Even if you don’t know much about it, it’s a really impressive artifact and worth checking out. As I noted, the museum is conveniently located, shows the fragments off fairly well, and seems not to be very crowded anymore, unlike the nearby Forum and Colosseum. For fans of ancient Rome or cartography, it should be a must-see. The outside garden area is also worth strolling through if you’re interested in Roman epigraphy, though if the sun is out and it’s even moderately warm, you may find that you don’t want to stay too long. On the other hand, in cooler weather it’s a nice place to simply stroll around, if only to escape the nearby chaos.

I’m glad to see the fragments are on display and also that this area of the city is being promoted, but I have a hard time shaking the feeling that a one-artifact museum like this isn’t going to be very successful. Maybe the west wing of the compound which isn’t part of the museum as it’s currently configured can help out with that. A space for rotating shows could be a good draw.

-

I was worried that the AC wouldn’t be able to keep up with the sunlight, which is why I went back on a hot sunny day. As I noted above, all was well, at least when there wasn’t a crowd inside. That said, I still think shades would be a good addition, if only to improve the viewing. ↩

Tags - Rome - museums - Celio - Forma_urbis - archaeology - classics