de vita sua

a blog

The Pyramid of Gaius Cestius - Measuring a side

by John D. Muccigrosso

I’ve been delving into the topic of measurement in the ancient world of late, more on the side of modern attempts at it, but also involving the way the ancients did their measurements, what units they used, and so on. I recently stumbled on a surprising (to me) example of the incorrect measurement of a rather well-known monument with an interesting metrological aspect.

Visitors to Rome will know one of the more unexpected ancient monuments, the funerary monument of C. Cestius in the form of a big white pyramid.

The pyramid has been at least partly visible since its construction in the late first c. BCE and was probably preserved, like the famous tomb of the baker Eurysaces, by being incorporated into the late-third-centry Aurelian walls of the city. In the early 1660s, Pope Alexander VII excavated and cleaned off much of the monument and explored its contents.

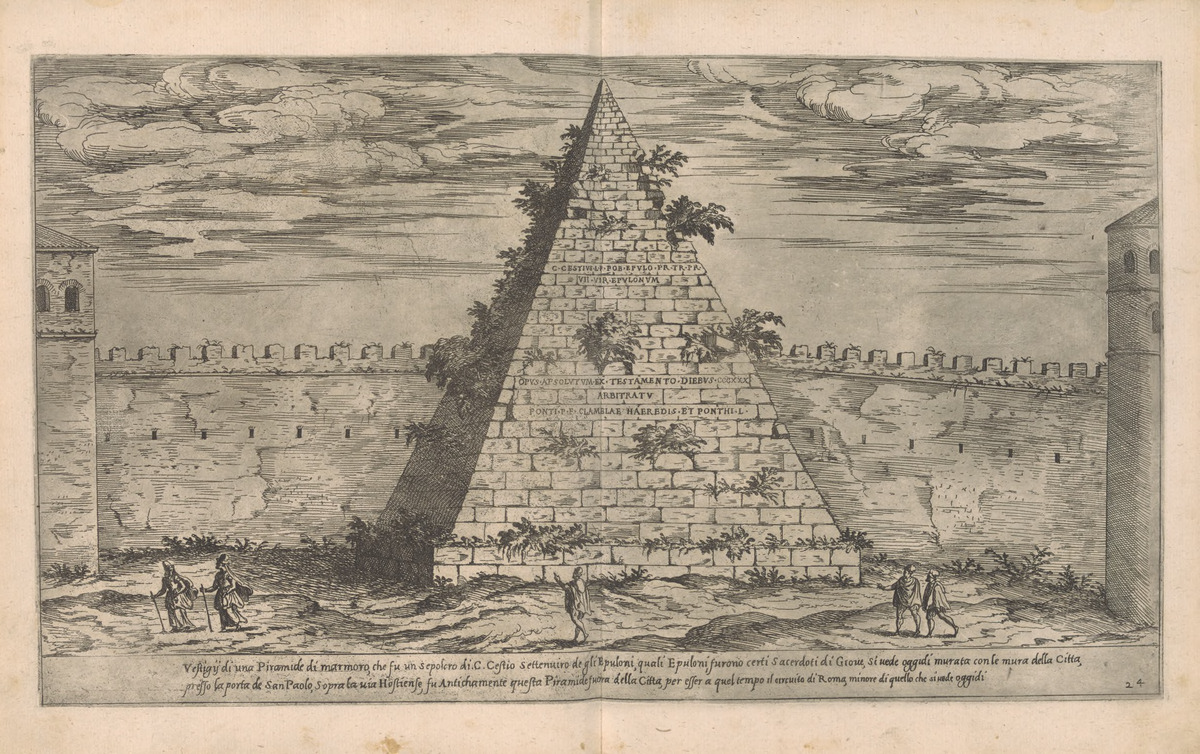

Alexander had the entrance that you can see in the photo cut into the western face of the tomb. It’s visible on Piranesi’s 18th c. drawing, too.

It also seems clear from comparison of the two images that in Piranesi’s time, the very bottom of the pyramid was still (again?) covered with soil. You can see that easily in the height of the bases below the two columns Alexander had re-erected at the corners of the pyramid. Despite this Piranesi made a detailed drawing of the foundations of the pyramid and also its plan, including a scale.

If you follow the link to the Wikimedia Commons version of that image and grab the biggest size, you’ll find that the 80 Roman palms on the scale take up 2,116 pixels, for a ratio of 26.45 pixels/palm or 0.0378 palms/pixel (rounding a tiny bit). The width of the western (ponente) side is 3,537 pixels or 133.7 Roman palms. So how big is a Roman palm? Apparently, about 22.32 cm (if we use the architect’s version, which seems like a good idea for Piranesi), making the length of that side about 29.8 m.

So that makes the pyramid interesting from the metrological perspective, because that’s basically 100 Roman feet, if we take the generally accepted length of that foot as 29.6 cm (0.2 is <1% error on 29.6).

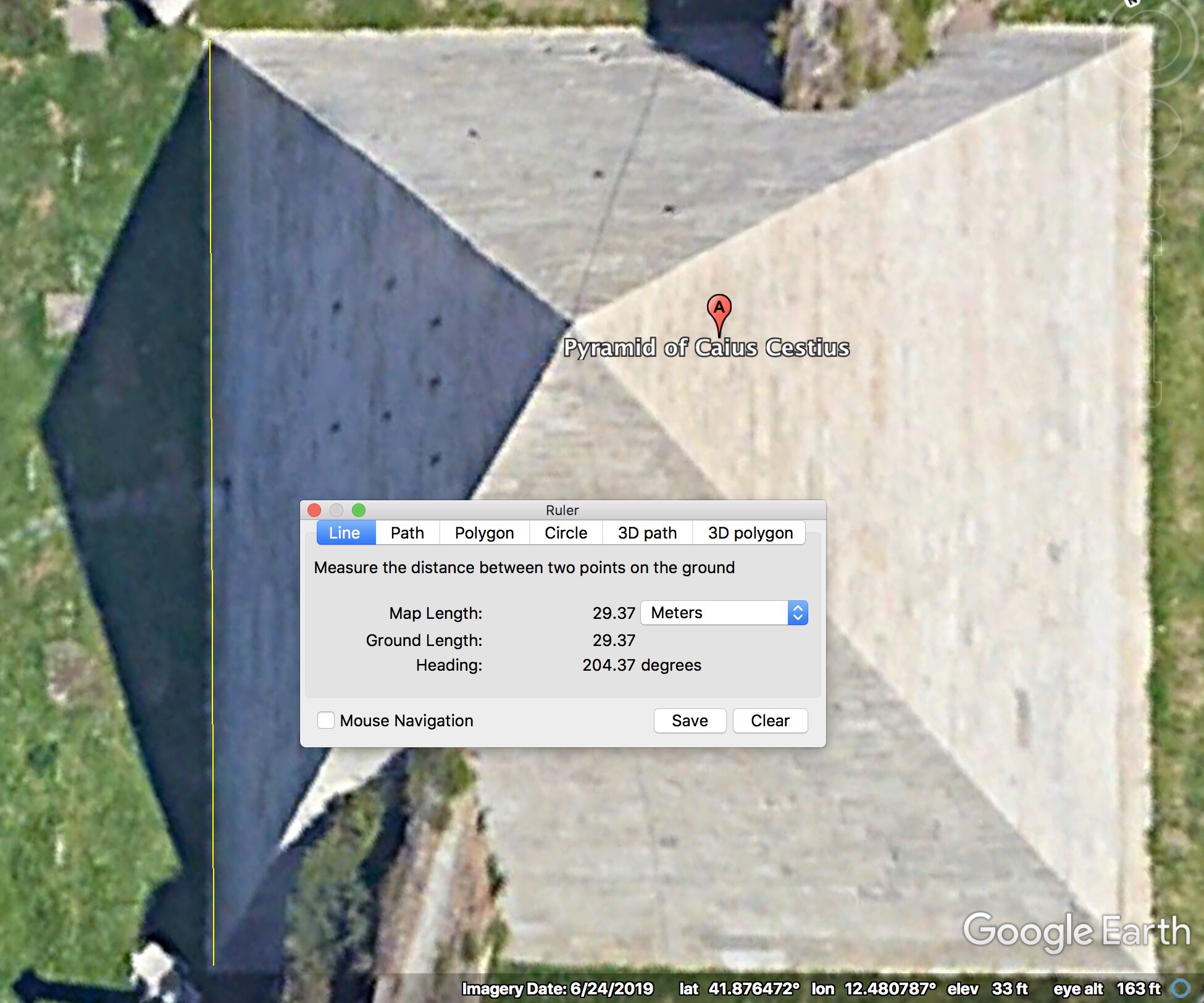

Thanks to the wonders of modern satellites and tech giants, we don’t have to take Piranesi’s word for it. I took a measurement of the western side of the pyramid via Google Earth and got 29.4 m, which to me is remarkably close to Piranesi’s number.

The height of the pyramid (which I can’t find an easy way to measure myself on-line) is said to be 37 m, or 125 Roman feet. That gives a height:base ratio of 1.25.

Why is it wrong in anglophone sources?

Now it gets a bit interesting. If you look up in the classic—if superseded—topographical work on ancient Rome (Platner, S.B., and T. Ashby. 1929. A topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. London: Oxford University Press, H. Milford), you’ll find the pyramid under “Sep(ulcrum) C. Cestii” where it says:

It is of brick-faced concrete covered with slabs of white marble, is 27 metres high and about 22 square, and stands on a foundation of travertine.

Well, that’s not right. In fact it’s not even close! 22 m is 74 Roman feet, more than 25% short. That should even have been obvious with the naked eye, especially since it’s almost exactly the length of a cricket pitch of 22 yd (and it’s odd that he uses “about” to describe the width, but not the height which was presumably a bit harder to measure). Platner had it right in his work on the same topic published 18 years earlier (Platner, S.B. 1911. The topography and monuments of ancient Rome. 2d ed., rev. enl. Boston : http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015011320457), where you can read under “Tomb of Cestius”:

It is about 35 metres high and rests upon a base of travertine 30 metres square.

So maybe it was Ashby. (Note that he puts the imprecision on the height, not the base.)

But in 1759 Matthew Raper wrote:

…Greaves’s measure of the monument of Cestius, whose side within the city (as he says in p. 151 of his works) is completely 78 feet English; which, reduced to Graham’s measure, is 77.84, and contains 80 Roman feet of 973 London parts each.

“An Enquiry into the Measure of the Roman Foot; By Matthew Raper, Esq; F. R. S.” Philosophical Transactions (1683-1775) 51: 774–823

And, though that’s closer to the correct measurement, it’s not right either.

Possibly Raper’s source John Greaves, who died in 1652, was not measuring the actual base of the pyramid since Alexander’s clean-up was years away, though this work of his was published in a 1737 edition mentioned by Raper (Miscellaneous works of Mr. John Greaves, professor of astronomy in the University of Oxford. 2 vols. London: Thomas Birch. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/mdp.39015063554847). And Platner and Ashby’s numbers give a height:base ratio of “about” 1.23, which is pretty close to the actual 1.25 we’d expect if the pyramid being measured were still partially interred (according to my high-school memory of equal triangles). But the pyramid doesn’t seem to have been buried deep enough for either measurement. Google Earth suggests that the difference in altitude between the modern—and so more or less late-Renaissance—street level and the base of the pyramid is about 4 m or 14 Roman feet. That would give us an 11% decrease in the base length, leaving us with 89 feet, still not close enough to either Greaves’ or Ashby’s numbers. We’d need about twice that (7.4 m) to get to 80 feet.

You can see what the Pyramid presumably looked like in 1544 in this drawing of Etienne Du Pérac, before the work of Alexander. He’s looking at the southeastern side of the pyramid, with the rounded Porta San Paolo to the right and the square bastion of the Aurelian wall to the left. Note that the square base that the pyramid sits on is clearly visible (unlike today; this isn’t the only drawing to show it), so basically the whole thing is exposed, at least on this side.

So what happened here? I’m not really sure. I could come up with some hypothesis (like maybe Ashby knew the ratio, mistakenly read 27 for 37 for the height and then calculated the base from that), but that would be just playing around. It’s very odd to me that two English-speaking works get a basic measurement wrong on such a famous and visible monument.

Note: I accidentally published this a few months(!) ago when I wasn’t paying attention while I updated my site. I’ve changed the date to reflect this intentional publication.

Tags - metrology - Rome